EVIDENCE: ONLINE

Past exhibition

Works

-

Anonymous, Ellen of Troy, 5th May, 1969

Anonymous, Ellen of Troy, 5th May, 1969 -

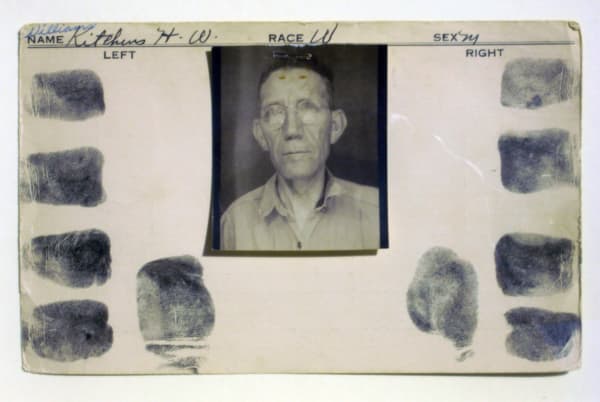

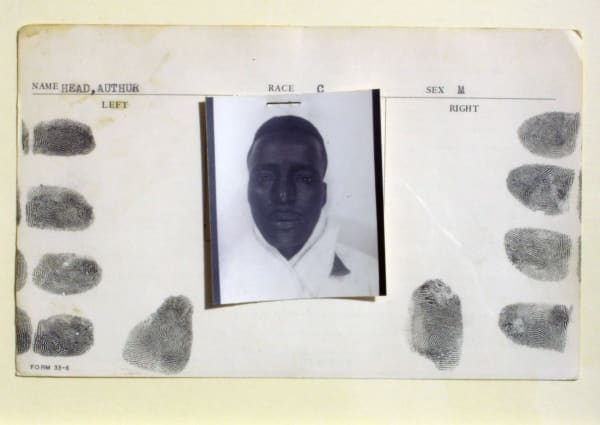

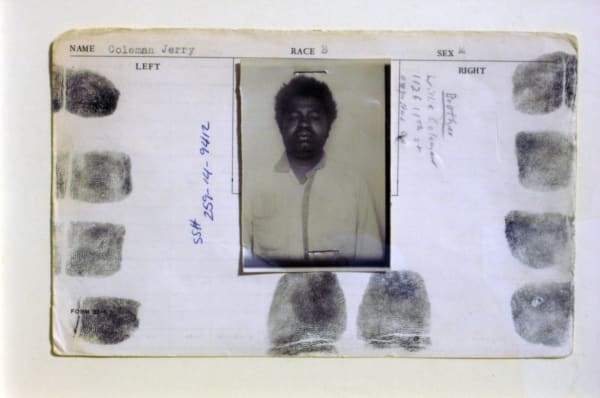

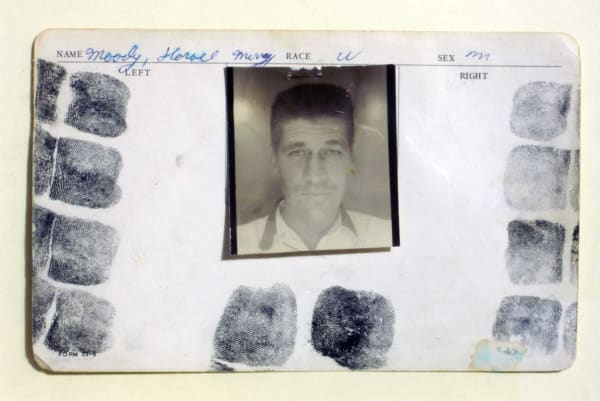

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1948

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1948 -

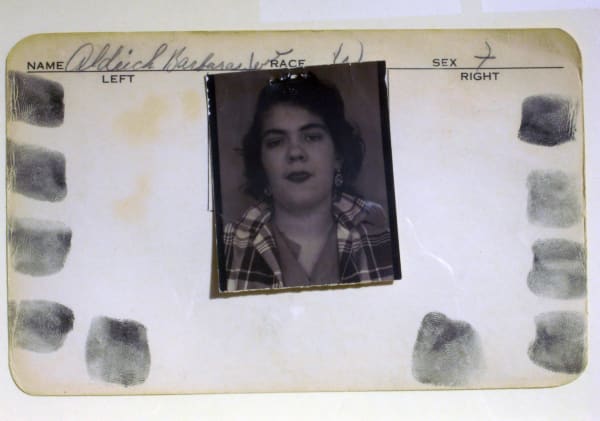

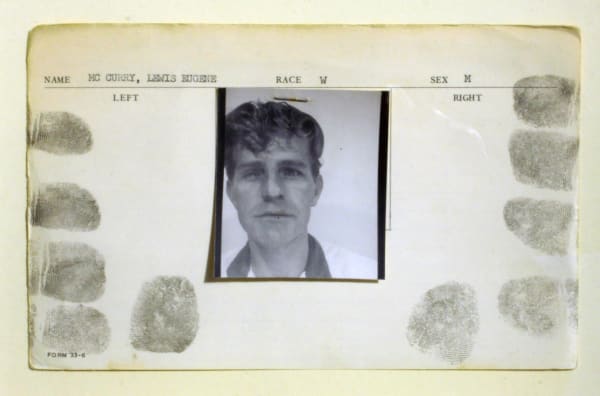

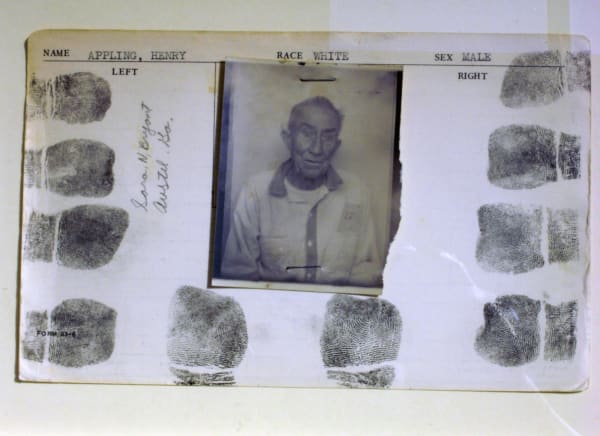

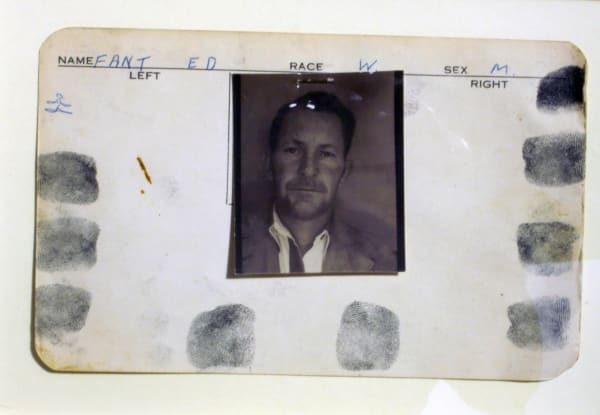

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1958

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1958 -

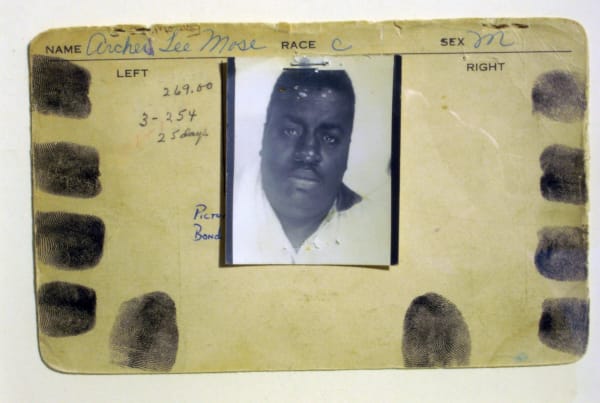

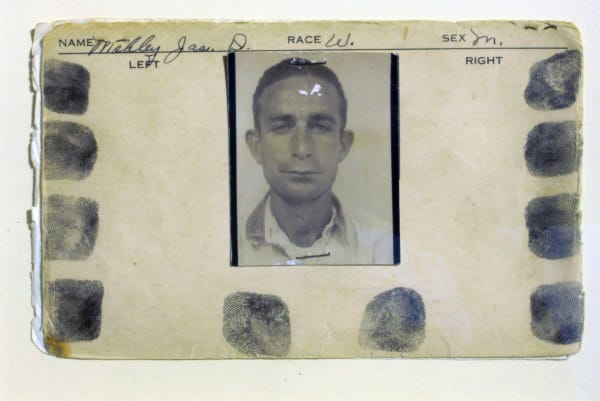

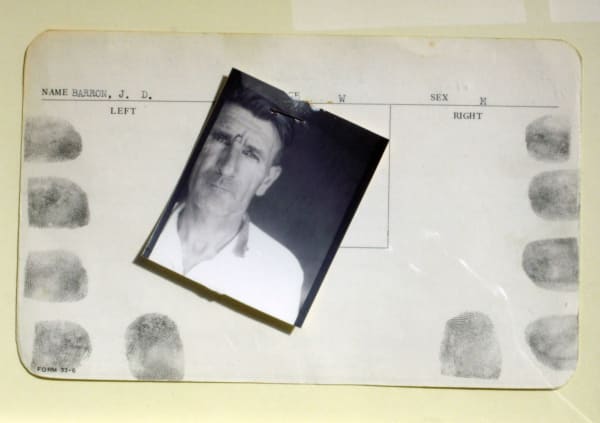

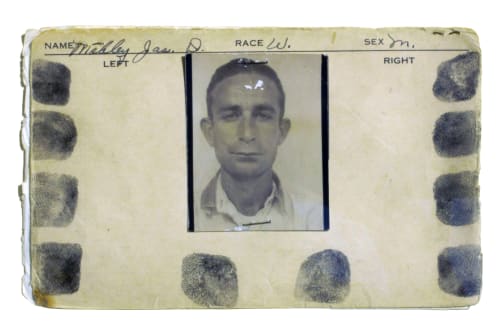

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1965

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1965 -

Anonymous, Close-up of 22 calibre bullets (extra long) taken from victim’s body (Mary Di Rocco murder)

Anonymous, Close-up of 22 calibre bullets (extra long) taken from victim’s body (Mary Di Rocco murder) -

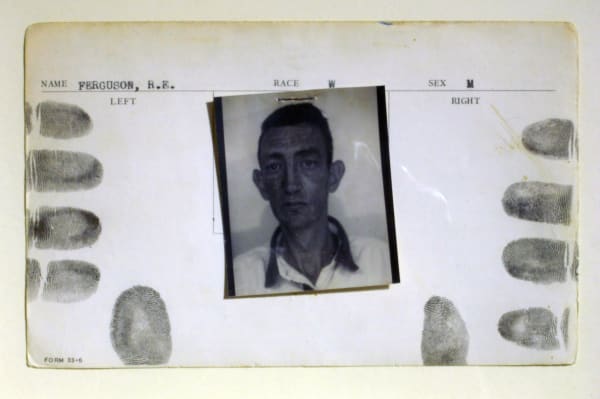

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1966

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1966 -

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1967

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1967 -

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1967

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1967 -

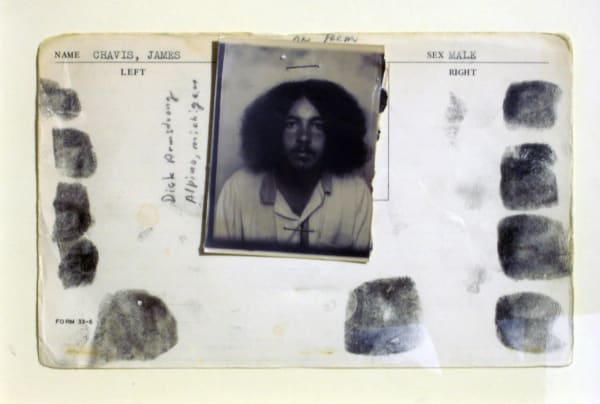

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1971

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1971 -

Anonymous, Weapons for murder!

Anonymous, Weapons for murder! -

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1972

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1972 -

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1972

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1972 -

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1971

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1971 -

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1966

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1966 -

Anonymous, Police firing range

Anonymous, Police firing range -

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1965

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1965 -

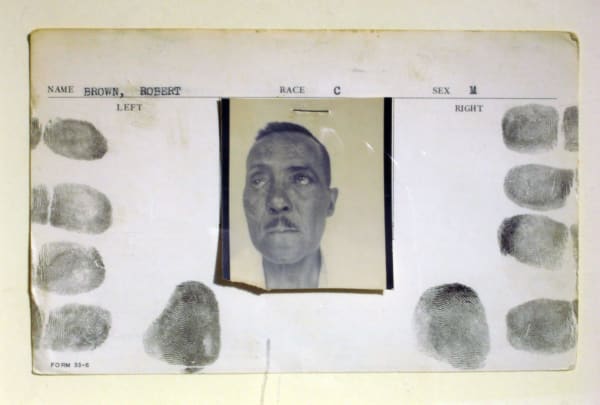

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1961

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1961 -

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1957

Anonymous, American police archive records - original photocard, 1957 -

Elizabeth, Kahle, Kleinhaus Hall = Vandalism, 1944

Elizabeth, Kahle, Kleinhaus Hall = Vandalism, 1944

Overview

In parallel with our current exhibition "? The image as question: an exhibition of evidential photography", we are presenting here a selection of crime related pictures including a series of photocards from the American police archive. Pictures such as these are known as mug-shots. Alphonse Bertillon, the grandfather of forensics, introduced this system into police practice. Details such a scars, tattoos and any other distinguishing marks would often be included on the photograph as part of the rap sheet and would, in turn, be used for identification and for possible future evidence.

Alphonse Bertillon’s anthropometric system had started to gain traction at the end of the 19th c, and in 1910 the first established police laboratory designed for the examination of crime scene physical evidence was launched by Edmond Locard. Even earlier than this Eugene Francois Vidocq, a criminal that turned to police detecton in the early 1800s, helped to organize the Sûreté, the detective bureau of the French police. His innovative techniques of record keeping, namely a card index system ushered in a new era of criminalistics. Criminalistics is designed to develop and interpret physical evidence; namely, to identify the actual substance, object, or instrument used in the surrounding events of a crime scene. Fingerprints, impression evidence, and trace evidence all fall into this category of expertise, but were not invented until the early 20th c. While forensic science, also referred to as forensic medicine or medical jurisprudence, encompasses some of the specialized areas such as serology; the study of blood, pathology; the study of the cause of death, and toxicology; the study of poisons. The need for forensic science professionals has evolved from the key elements of a crime scene, ideally, linking the victim to the perpetrator and exonerating the innocent. The need for experts to identify and individualize the items of interest from the crime scene is the foundation for solving the crime. An interesting approach to a crime scene re-enactment is to remember a simple key fact from Nickell and Fisher’s book titled Crime Science, Methods of Forensic Detection, “all objects in the universe are unique”.

Part of the fascination with all photography is that the medium is firmly grounded in the documentary tradition. It has been used as a record of crime scenes, zoological specimens, lunar and space exploration, phrenology, fashion and importantly, art and science. It has been used as ‘proof’ of simple things such as family holidays and equally of atrocities taking place on the global stage. Any contemporary artist using photography has to accept the evidential language embedded in the medium.

News

Video